18 May The Four Horsemen that will end the Bull Market

As published in News24 on 12 May, 2021 by Pieter Hundersmarck

“And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was Death, and Hell followed with him.”

– Johnny Cash “When the Man Comes Around”

History is full of valuable lessons.

Because things rarely repeat exactly as they did in the past, the lessons are more general than specific. We end up with ‘rules of thumb’ to abide by, rather than clear cause and effect relationships.

Such is the case for bull and bear markets. We know that when there are no recessions, people get over-confident. When they get over-confident, they take on too much risk. When risk accumulates, it leads to recessions.

Bull markets ultimately give way to bear markets. Understanding why this happens can provide investors with the greatest opportunities for gain or loss.

But what triggers a sell off? Does it start in the stock market or the economy? Is it something we can analyze and learn from? History has a few rules of thumb for us.

Historically, the trigger for a stock market crash or correction comes in one of four ways.

The first possibility is through a rise in interest rates.

Rising rates throttles economic activity. By changing the price of money, and thus the price of risk-taking, Central Banks raise rates to slow the economic machine, and indirectly, the stock market.

Slowing the economic machine slows the rate of growth for all businesses. Equity valuation multiples (the P/E ratio) contract as lower growth prospects lead investors to assign lower multiples to shares, further decreasing share prices.

The slowing economy, and the resultant effect on earnings growth and lower equity valuation multiples are only the beginning of the story, however.

Rising interest rates increase the cost of buying on margin. An inability to meet margin calls causes a great unwinding of leveraged positions, fueling losses and creating panic. This creates a knock-on effect as investors and speculators alike sell for risk management and loss reduction purposes.

In this scenario, all stocks get crushed. The most popular growth stocks sell off because a larger proportion of their value sits in their “long-term value”, as opposed to the economically sensitive stocks where a lot of the value sits in the front-end of the discounted cash flows. However, large liquid stocks (or ‘safe’ stocks) suffer too, as their very safety and liquidity make them the easiest to sell to raise cash to cover margin calls.

The slowing economy, precipitated by rising interest rates, was the major factor in the stock market crash of 1929, a view shared by the most knowledgeable students of the period, including Keynes, Friedman and Schwartz, and other leading scholars of both the Depression era and today.

The second possibility will occur via a loss of faith, and self-perpetuation thereof, in the continued rise of the market.

This type of crash can happen through the expectation, and not necessarily the manifestation, of a rise in rates or the advent of inflation.

An example of this can be found in the ‘taper tantrum’ of 2013, as well as the fourth quarter of 2018. In the latter case, the Federal Reserve governor Jerome Powell made statements alluding to a gradual rise in interest rates from the fourth quarter of 2018, which investors took as a signal that the Fed would no longer support asset prices (and the debt underpinning those assets).

Investors panicked, and the S&P 500 fell seven percent in October 2018 and accelerated those losses into November, leading to the index’s worst December performance since the Great Depression.

The third possibility is through a transmission mechanism to stock markets from a vulnerable part of the economy, normally the housing sector.

Using the example of housing, a run up in property prices, combined with low interest rates and forbearance on risk management by the banks lead directly to the late 1970s housing crisis as well as the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008.

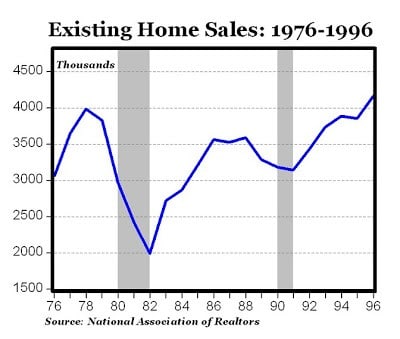

In the former example, from a peak of four million existing-home sales in 1978, the market halved over the next four years, troughing in 1982 at 2 million sales (see chart). It took almost two decades, or until 1996, before home sales exceeded the 1978 level of 4 million units.

Bubbles in real estate markets are more dangerous than stock market bubbles.

Historically, stock market crashes occur on average every thirteen years, last for two and a half years, and result in about four percent loss to GDP. Housing price busts are less frequent, but can last nearly twice as long and lead to output losses that are twice as large according to the IMF.

The Global Financial Crisis was related to the bursting of real estate bubbles that had begun in various countries during the 2000s.

The fourth is war.

Conflict creates enormous uncertainty, and the market responds poorly to uncertainty. Conflict creates winners and losers. On the winner’s side we see increased government spending, monetization, higher inflation and increased state intervention. On the loser’s side we see financial and social ruin.

Although global conflict seems out of the question to most of us, it always does, right up to the point that it happens. A conflict between the world’s previous superpower (the US) and the world’s future superpower (China) presents one such possibility.

How do we prepare?

The most famous prediction of the Wall Street crash of 1929 was made by Roger Babson. On September 5, 1929, he gave a speech saying, “Sooner or later a crash is coming, and it may be terrific.” Later that day the stock market declined by about 3%, a decline known as the “Babson Break.” The Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression followed two months later.

Babson was a prolific writer and thinker, and he had “Ten Commandments” he followed in investing and encouraged his readers to do the same. These were:

- Keep speculation and investments separate.

- Don’t be fooled by a name.

- Be wary of IPOs.

- Give due consideration to market ability [the wisdom of the market].

- Don’t buy without proper facts.

- Safeguard purchases through diversification.

- Don’t try to diversify by buying different securities of the same company.

- Small companies should be carefully scrutinized.

- Buy adequate security, not super abundance.

- Choose your dealer and buy outright (don’t buy on margin).

Babson understood that investment and speculation could co-exist. He advocated that a wariness of leverage, new issues (IPOs), and ‘well regarded names’ would hold his readers in good stead. He advocated humility through ‘due consideration’ in the market’s ability, and was a big believer in diversification.

All of these rules – all of them – apply today. There are very few ways to protect against a market bubble. However, one can diagnose the signs that a bubble is on the horizon and prepare accordingly. A properly diversified portfolio of stocks, bought ‘outright’, in non-speculative issues will serve investors well.

About Pieter Hundersmarck:

Pieter is a fund manager and member of Flagship’s global investments team.

Pieter has been investing internationally for over 13 years. Prior to Flagship, he worked at Coronation Fund Managers for 10 years in the Global and Global Emerging Markets teams, and also co-managed a global equities boutique at Old Mutual Investment Group. Pieter holds a BCom (Economics) from Stellenbosch University and an MSc Finance from Nyenrode Universiteit in the Netherlands.