15 Sep Six Typical Profit-making Strategies for the Fundamental Investor

As published by Sanlam Glacier on 10 Sept, 2021 by Kyle Wales

Investment cases are distinguished depending on the market inefficiency they aim to exploit.

While each is unique, investment cases can be grouped into a surprisingly small number of fundamental investment strategies. The profit to be reaped from each of these strategies is in turn dependent on which among the three return drivers from a share expresses itself the strongest. These three (and there are only three!) return drivers are:

- the dividend yield a share pays on the day you buy it (hereafter referred to as “yield”).

- the rate at which a share can grow its earnings (“growth”).

- the change in the multiple on earnings (or book value) that the market is prepared to pay for a share (“re-rating”).

I have had the privilege of training up a number of investment analysts over the years and the first lesson I teach them is how to distinguish these strategies as well as the potential pitfalls the aspirant investor needs to avoid with each.

These are the six strategies:

Strategy 1: The Steady Compounder

The investment case for compounders is normally premised on a low but secure dividend yield, together with a low but stable growth rate.

The dividend is reasonably secure because the goods or services they sell enjoy constant demand regardless of the business cycle. Earnings growth is low but predictable, largely due to some form of pricing power which allows them to put through cost increases ahead of inflation and expand their profit margins.

A good example of a compounder is a consumer staples business like Unilever. In its golden years from 2005 to 2015, Unilever delivered a compound return of 10.95% p.a. versus the MSCI ACWI return of 5.35%.

The problem with secure compounders today is that the market mostly gives them credit for being such. If one uses consumer staples businesses as an example, they trade on very high valuations for very pedestrian growth. A stock like Unilever, for example, trades north of 20 times earnings even though it has only grown its “core” operating profit at a CAGR of 3.6% over the last 5 years.

| Unilever | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 5-year CAGR |

| “Underlying” Revenue growth | 3.7% | 3.1% | 3.2% | 2.9% | 1.9% | 3.2% |

| “Core” Operating Profit | € 8,624 | € 9,400 | € 9,463 | € 9,947 | € 9,367 | 3.6% |

Due to the high multiple and lack of underlying fundamental support, the share price return has been predictably pedestrian (+3.6% p.a.) over five years. If the compounding algorithm can reignite, this will change.

Compounders are vulnerable to interest rate rises. Their yield, no matter how low, is very attractive in our current yield starved world (i.e., a world where interest rates are low) but it becomes far less attractive should interest rates rise. When this happens, these stocks, which have already delivered paltry returns over the last five years, could de-rate further.

Strategy 2: The High Yielder

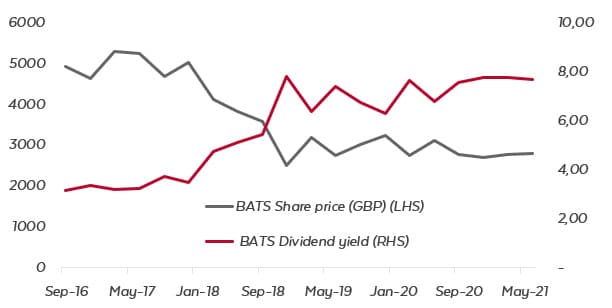

A high yielder is a stock which has a high initial dividend yield. An example of a high yielder would be a tobacco company like British American Tobacco (BAT).

Normally, the reason a high yielder trades on a high initial dividend yield is because the market has concerns over how sustainable that dividend yield is. In the case of BAT, for example, there are regulatory concerns around the product they sell together with doubts around whether their portfolio of next-generation products can offset the volume decline in their combustibles business.

So where can an investment like this go wrong? Quite simply, when the thing that the market is concerned about, comes to pass. In the case of BAT, regulators in the US mooted a ban of menthol cigarettes, which comprise a large part of its combustible portfolio, because they view menthol cigarettes as a gateway for teenagers to start smoking. Uncertainty in the revenue growth resulted in a higher dividend being demanded by the market. This led to the share price decline of the past five years (-10%) which was only slightly compensated for by the dividend yield, leading to an annualised 3.8% return.

Strategy 3: The growth stock

Growth stocks are typically active in nascent markets or they have compelling product offerings (but very low market shares) in more mature markets. Their earnings are depressed because their revenue bases are currently small and their profit margins are low because they are re-investing what they make in order to grow faster.

A growth stock can make an attractive investment because a stock which trades on a very high multiple today can grow into that high multiple fairly quickly, if it is able to grow its earnings at a very high rate. A business growing its revenues at 50% p.a. will be almost eight times its current size in five years’ time if it maintains that rate of growth.

An example of a growth stock is Endava. Endava sells professional services to businesses in order to help them handle digital disruption within their industries. Demand for their services is currently very high and it is hoped that they will expand their market share in the professional services market which tallies in the hundreds of billions annually. As a consequence, they trade on a very high multiple of their current earnings.

The problem with markets is that growth alone is not good enough. When the market expects a company to grow and it delivers upon that growth you often don’t make money because that growth is already priced in.

Conversely, if it fails to deliver upon that growth the falls can be quite dramatic.

Be careful when the market anticipates very high rates of growth. Just like the power of steady compounding has been under-appreciated in the past, the likelihood that a business can compound at very high rates of return for long periods is often over-estimated. History teaches us that the likelihood of this happening is extremely low.

Strategy 4: The net asset value “NAV” unwind

NAV unwinds are specific to holding companies, as investment holding companies typically trade a discount to the sum of their parts.

The reasons for this are twofold. The first is complexity. It takes effort to understand a business with many disparate parts and market participants typically fail to take the time to do so. Secondly, with investment holding companies there is an additional layer of complexity and expense that is added at the holding company level, which acts as a tax on the cashflows from the companies that sit below it.

Very seldom does a holding company trade close to its NAV (and even more seldom at a premium to its NAV). In the rare occasions where it does, it is normally a vote of confidence in the person that is allocating capital at the top (such as Warren Buffet at Berkshire Hathaway).

As a result, my experience with NAV discounts is that they tend to persist unless the management of the holding company have a stated strategy of breaking up the holding company structure and distributing the proceeds to investors.

A good example of a failed NAV discount unwind in the local South African market is Naspers. An investment in the underlying holding of Naspers (Tencent) has delivered 31.4% in USD per annum over the past ten years. An investment in Naspers has delivered 19.9%.

Up to now, Naspers has been an enormous failure as a NAV unwind investment case. NAV unwind investment cases require a clear understanding of what will cause the discount to unwind, and what the probability of that event is. Don’t allow yourself to be seduced by this theme unless you afford yourself a wide enough margin of safety that you can make money even if the discount doesn’t close completely.

Strategy 5: The turnaround

A turnaround, like the NAV unwind, is premised on re-rating. The turnaround is a business whose fortunes took a turn for the worse leading to its earnings to decline. Consequently, it trades on lower multiple of earnings than it did in the past.

People investing in a turnaround are betting that the company’s fortunes can be revived and this will cause its earnings and the multiple it trades on to expand. When successful, a turnaround can be incredibly lucrative.

However, there are almost always very valid reasons why a company’s fortunes took a turn for the worse. Mostly the reasons relate to the quality of the business and/or its management. In many cases the quality of a business or management cannot be altered and, even when it can, it may take far longer than one would expect, because things like a company’s culture are notoriously difficult to change.

A good example of a turnaround is Intel. Intel used to have a monopoly in the market for PC logic chips. Intel experienced problems when the rise of smartphones eroded demand for PCs (and consequently PC logic chips) and TSMC, a Taiwanese company, took process leadership away from it, TSMC could make better logic chips than Intel could. Those who own Intel today believe it can regain process leadership and tilt its business model so that it becomes less reliant on PCs.

A turnaround is an investment behind change. It requires in-depth research, with clearly articulated reasons why the turnround is forthcoming. Go in with open eyes and do your homework, for example, if there is a new management team in place, have they pulled off something similar before? Why is growth going to pick up now, when it hasn’t in the past?

Strategy 6: The cyclical

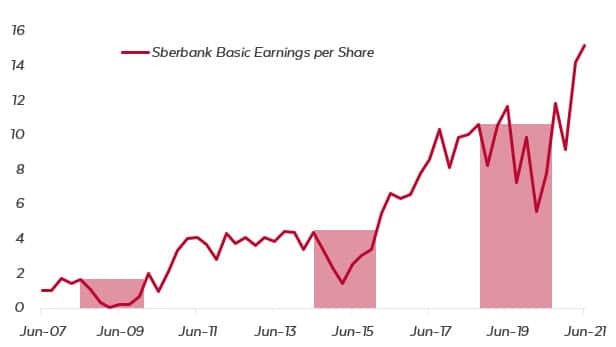

Cyclicals are companies whose earnings exhibit an amplitude because demand for their products varies over a business cycle. As with all types of investment cases, there are a few tricks here as well. Though it may seem counterintuitive, cyclicals are normally expensive when they trade on low multiples and normally cheap when they trade on high multiples. An example would be a bank, like Sberbank, which is the largest bank in Russia.

When the economy is performing well, banks grow their loan books very quickly and the level of provisions they hold against these loans declines. This is when their profits and share prices peak. It is also the point that they trade on low multiples of high earnings.

When the business cycle turns (as it always must, indicated by the red shaded areas in the chart above), loan growth slows and banks are forced to raise provisions on loans that default. This in turn is when their profits and share prices trough and it is also the point at which they typically trade on high multiples of low earnings.

Investors who buy bank stocks when their share prices trough do well as the cycle improves and their share prices rise.

Knowing which playbook your investment case fits can help you avoid easy mistakes

There is an increasing cohort of retail investors for whom fundamentals seem to matter less and less. However, fundamentals do matter, especially if you wish to achieve market-beating returns over extended periods of time. Chief among these is knowing which playbook your investment case fits.