22 Nov A recessionary tale: caution is advised when assuming a soft landing

As published in Business Day on 27 November 2023, Philip Short discusses the indicators that still point to a hard landing with Nompu Siziba on Moneyweb.

The markets entered the fourth quarter with renewed optimism, rewriting the higher-for-longer interest rate narrative and buoyed by a positive earnings season in the US. But, we remain wary of becoming overoptimistic, and believe the question we need to interrogate as we finish out the final months of the year is: “How likely is it that the world economy will experience a soft landing, and what would that mean for equity markets?”

Optimism on the outlook for companies with AI capabilities set the stage earlier in the year, with Nvidia putting out a brilliant, market-beating set of results that laid the foundation for this optimism. That led to certain heavy-weight companies rallying, pulling the rest of the market with them, and strong third-quarter results from Amazon and Meta kept the momentum going.

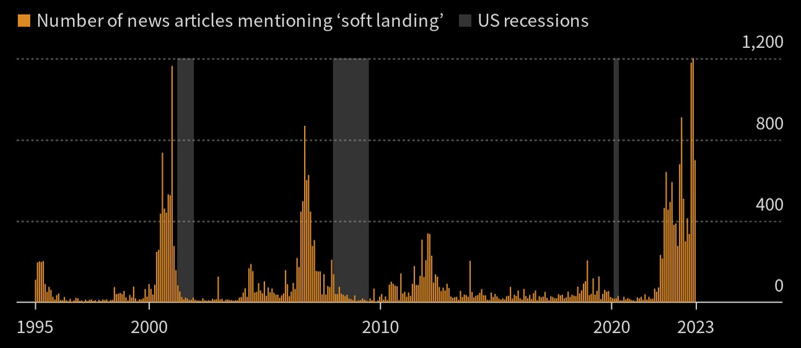

At the same time, we saw the US post decent real GDP data in July and August, both above 2%, and inflation continued coming down. Consumer spending was positive, but only just. Market analysts have increased their earnings forecasts for US companies. Ergo, the calls for a soft landing or no recession grew louder. This should not, in itself, be a source of comfort, as the voices predicting soft landings were loudest right before the actual recessions in 2001 and 2008.

Chart 2: Soft landing hopes and hard landing realities, Bloomberg

It is tempting to get sucked into market narratives as much as it is comfortable to stick to your original views. New data needs to be tested, assumptions must be challenged, and robust debate should be encouraged.

Digging deeper

Three macro backdrops occurring in the third quarter have made us wary of assuming a soft landing:

- Stronger oil price: Brent oil increased 25% in price in the quarter alone. Although Energy on its own is excluded from the Core Inflation measure, it still has a second-round effect on almost all goods. The oil price was primarily driven by OPEC+ supply cuts, which are with us until year-end, at least. With US oil reserves and inventories at multi-decade lows, this is a concern and could support oil prices as the US builds up strategic resources. The war in Gaza has helped muddy the waters.

- The US dollar strengthened: this might help US inflation at the margin, but it is a drain on global liquidity and makes everything more expensive for all other nations. Commodities are priced in US dollars, as is a significant portion of global sovereigns’ debt.

- US 10-year bond yields have whipped higher, a warning signal for bond and equity investors alike. There are a number of reasons why yields would be higher. Stripping out the one possible reason, namely global growth coming in higher than expected, which it hasn’t, none of the remaining reasons are positive (higher inflation expectations, concerns about government debt and/or risk aversion regarding US safety assets).

Other US indicators pointing to a recession are an inverted yield curve, weak global PMIs, tighter corporate lending activity (evident in tighter lending standards and at higher spreads), rising corporate bankruptcies, declining year-on-year federal tax receipts, and more.

A big theme we are also witnessing is the lagged effect of monetary policy tightening. As the Federal Reserve increases interest rates, the full effect is only felt ~18 months later. A great example of this is looking at US corporate balance sheets.

US corporate balance sheets

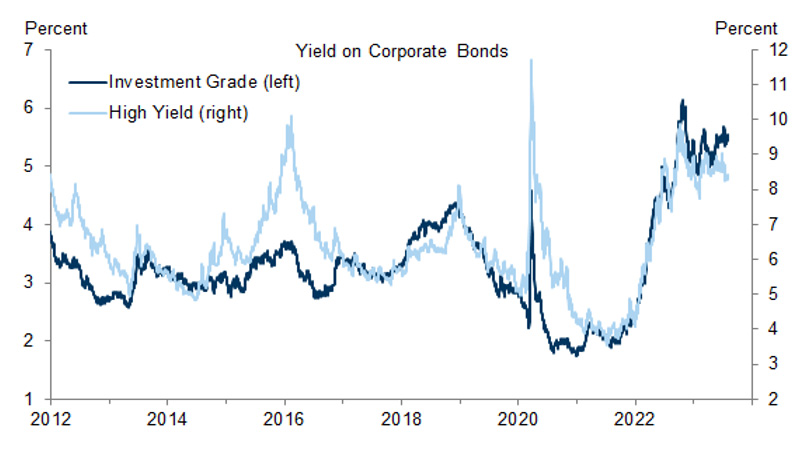

Net interest paid by US corporates has been flat since 2021 and below pre-pandemic levels. How is that the case when interest rates on Investment Grade and High Yield debt have doubled since 2021? Two reasons: 1) Corporates refinanced their debt during the pandemic at lower rates, and 2) corporates have increased their net cash levels over the years, such that they are now earning greater interest income on that cash as interest rates have risen.

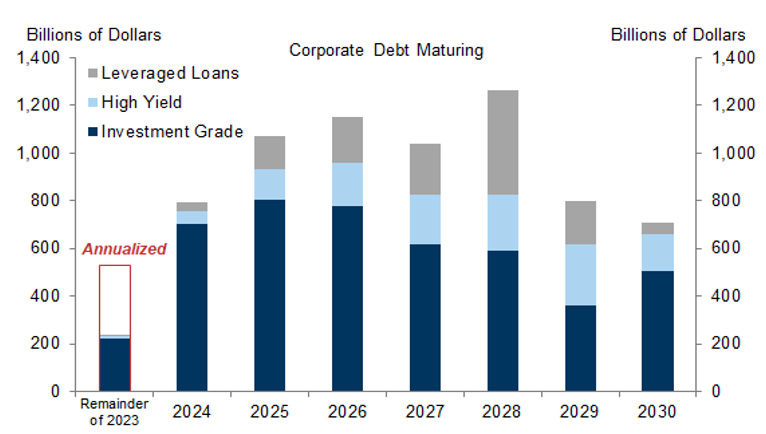

The lagged effect occurs when existing debt matures over time and needs to be refinanced at higher rates. That first tranche of debt that needs to be refinanced is coming due and will grow over the next few years.

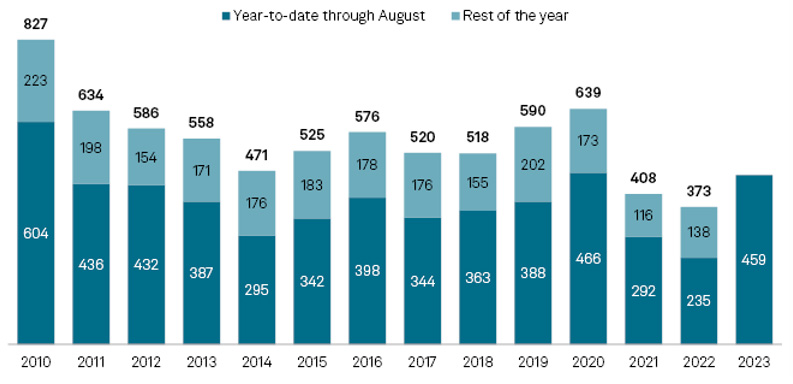

Chart 3: Size of corporate debt maturing until 2030 (in USD billions), Goldman Sachs

The result is a larger amount of debt being refinanced at much higher rates, which increases net interest expenses materially. Interest rates on corporate debt have doubled over the last 18 months.

Chart 4: Interest rates on corporate debt from 2012 to August 2023, Goldman Sachs

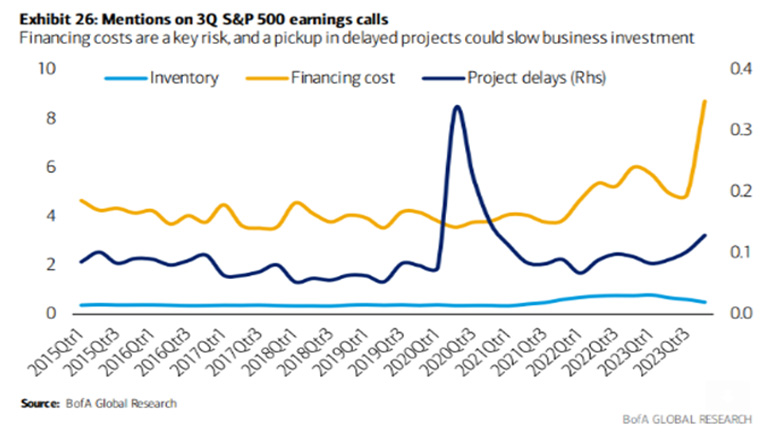

We are also now seeing anecdotal evidence of further debt issues arising on third-quarter earnings calls with management of S&P500 companies, as evident in the graph below.

Currently, bankruptcies are on the rise, due mainly to higher interest rates. If inflation stays high, rates will stay higher for longer, and more bankruptcies will occur. This will lead to higher unemployment, lower economic growth, and even more bankruptcies.

Chart 5: US bankruptcy filings by year, S&P Global

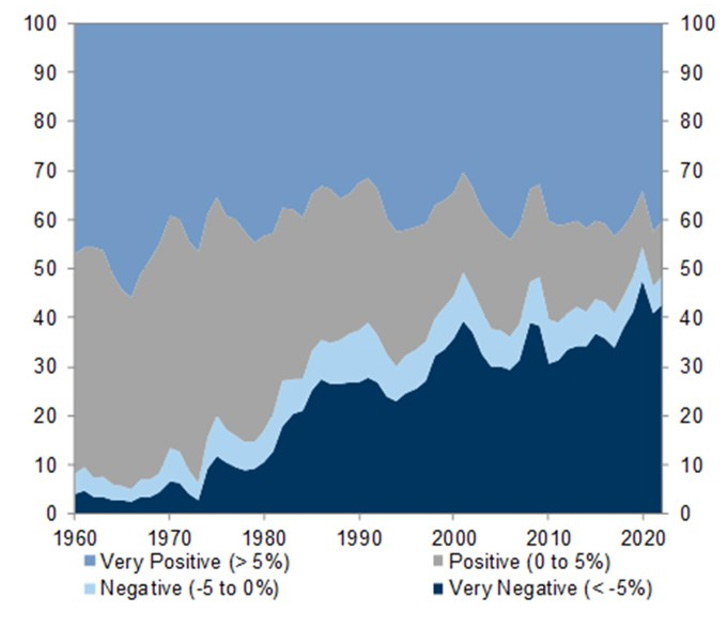

Finally, we think the outlook for financial markets and the global economy is potentially worse than it appears, because we’ve lived through a period of cheap money for too long. US interest rates have been declining ever since the early 1980s to the point where some government bonds were yielding negative rates. Ultra-low rates allow unproductive companies to survive for longer than is warranted. With the higher rates we are experiencing today, these “zombie” companies will get burnt and roll over. It is startling to see that nearly half of all publicly listed companies in the US are making a net loss.

Chart 6: Share of all publicly listed firms by profit margin (in %), Goldman Sachs

Together, these signals justify a cautious outlook, backed up by careful analysis of the underlying factors driving macro-economic and company fundamentals, instead of the growing conviction that a soft landing is possible and, indeed, the most likely outcome for the global economy and the equity markets.

In anticipation of a hard landing, investors should consider well-priced defensive businesses whose earnings should be least affected, such as Coca-Cola Femsa (Mexico), UnitedHealth (USA), and Thales (France). Coca-Cola Femsa, a Mexican soft drinks bottler, is exposed to a strong macro-economic backdrop, being Mexico and parts of South America, whose economies are benefiting from the US moving its imports away from China and more towards Mexico. In its recent results, Femsa reported strong growth in volumes and pricing, something very few other global consumer staples have been able to do. It trades on an undemanding 14x forward P/E and a 4% dividend yield. In a global recession, Mexico as a country should outperform other geographies, given idiosyncratic macro tailwinds. In addition, as a product, consumers will cut back on more discretionary spend before they stop drinking Coke and other soft drinks.

UnitedHealth, the US’s largest healthcare provider, is exposed to most services in the healthcare value chain, from hospital services to pharmacare. In a recession, consumers will always prioritize self-care and healthcare services before discretionary spend.

Thales, a French aerospace and defence contractor, has governments as its main customer. Heightened global and sovereign security notwithstanding, Thales has a multi-year order book that is reliably filled during the good times and the bad. Given current geopolitical events has only benefited the likes of Thales.

People will always drink soft drinks, get sick, and unfortunately there will always be the threat of war. Exposure to a mix of these defensive businesses affords you the benefits of global diversification and across different sectors. The Flagship IP Worldwide Flexible Fund holds the above stocks in its clients’ portfolios.