18 Oct Geopolitical Conflicts and Global Markets

As published in Glacier and Citywire on 16 October 2024

By JD Hayward

- Geopolitical tensions are on the rise across the globe. Aside from the current armed conflict in Ukraine, Israel’s operations against Hamas and Hezbollah, and various other internal or regional conflicts, tensions are also on the rise in the East, as China expands its claims over the disputed South China Sea, as well as its increasingly aggressive rhetoric towards Taiwan.

- A number of countries, especially those forming part of NATO, are revisiting their outlook on national security and subsequently their defence budgets. Despite prior commitments, only 60% of members are actually reaching their spending goals.

The last few decades have been relatively peaceful for much of the Western world and investors have been able to benefit from one of the longest periods of globalization and peace the world has ever seen. Many developing countries, however, have not enjoyed a similar era of calm. The Middle East and Africa have been particularly hard hit, with both experiencing bouts of conflict over a prolonged period. Today, things are looking slightly different, with much of the developed world again facing the prospect of war. A little over two and a half years ago, in February 2022, armed conflict returned to continental Europe as nearly 200 000 Russian soldiers crossed the border from Russia into Ukraine. They thought it would be a swift march to victory in Kyiv. Today, the battle still drags on and hope of a resolution seems distant.

The war in Ukraine and the fighting between Israel and Hamas, on the cusp of entering its 2nd year after Hamas launched attacks in October 2023, are by far the most dangerous in terms of the risk of spilling over into a much larger conflict. They are, however, by no means isolated incidents. According to the Geneva Academy of International Law and Human Rights, there are currently more than 100 instances of armed conflict, both internal and cross-border, worldwide.

There are also several situations where tensions are simmering below the surface. Front and centre would be Beijing and its increasingly aggressive rhetoric towards Taiwan and other “foes” in the South China Sea. While most of these conflicts are unlikely to spill over into large scale warfare, there is no looking past the fact that, today, the world is again facing the prospect of confrontation between nuclear-armed powers, with Russian President Vladimir Putin warning, on several occasions, that its nuclear forces are in “full readiness”.

Despite the increased volatility, markets have largely shrugged off the potential economic impacts of these events. There was a brief bear market in 2022, mainly due to a combination of Russia’s invasion, interrupted supply chains, higher inflation and tighter monetary policy, but these concerns seem to have been mostly relegated to the past. The benchmark S&P 500 has returned roughly 30% over the last 3 years (measured from before the bear market), and nearly 60% since the troughs of October 2022.

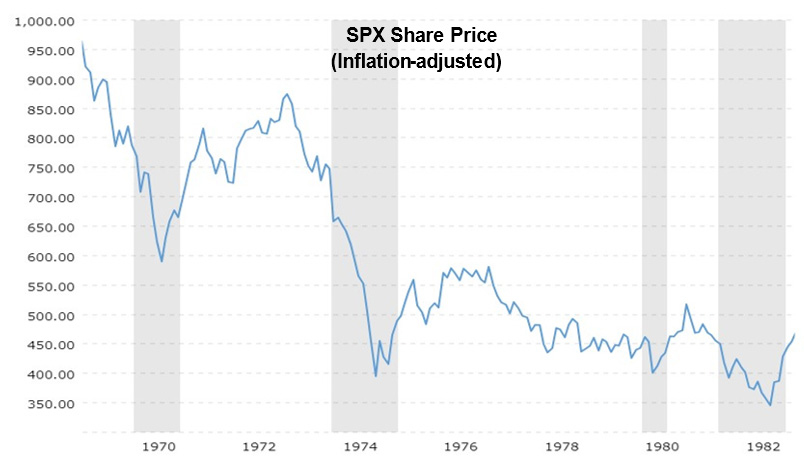

Regional conflicts leading to higher oil prices is a story that has been seen before. The OPEC-led oil embargo of the 70’s directly led to higher energy prices, driving inflation and interest rates to extreme highs in the US and beyond. The results for capital markets were disastrous, as the S&P 500 declined by more than 60% on an inflation-adjusted basis.

Source: Macrotrends

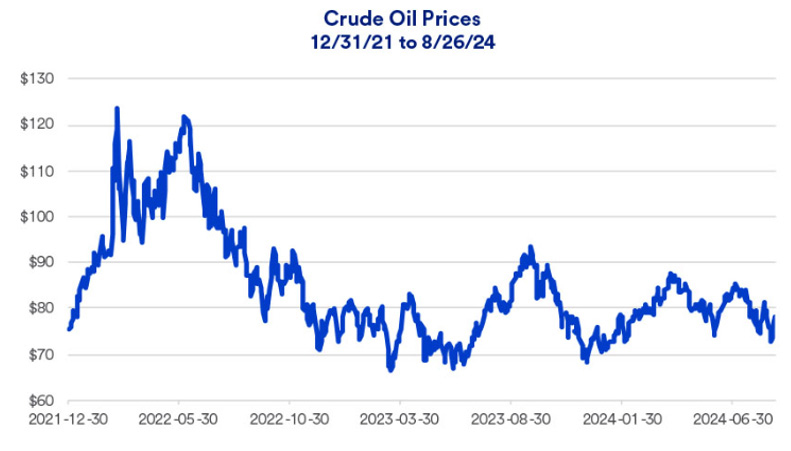

A key difference between the 70’s and the current environment is the rate with which oil prices have normalized. After a sharp run-up to more than $120/barrel, investors saw that among other factors, Russian oil was still finding its way into the market at nearly the same rate as before, and so the global supply/demand equation was not as unbalanced as originally feared. By the end of 2022, oil prices were back below $80/barrel and have largely remained in that region ever since, bar a brief run to $90 in the latter part of 2023.

Source: US Energy Information Administration, Federal Reserve Bank

Key contributors to this have been two warmer than normal European winters, leading to subdued demand for Russian oil and gas. Aside from the fact that another European winter is enroute, today there is a much more threatening factor to consider – the involvement of Iran and its proxies in a wider regional war in the Middle East. This would have the potential to materially change the supply/demand equation, and currently this looks more likely than at any point in the recent past.

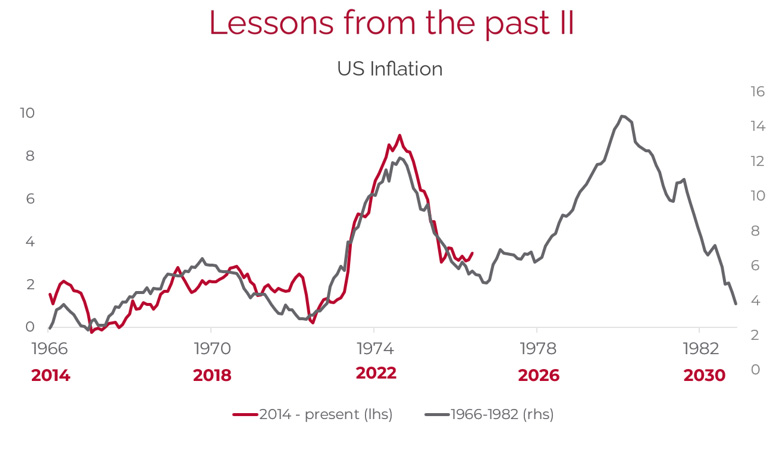

The role of Iran and its proxies leading to higher oil prices, and subsequently higher inflation, does not only sound like a familiar story, but it also looks familiar as well…

Source: Bloomberg, Flagship Asset Management

What does this riskier era mean for investors?

After the cold war, the West has experienced an era referred to as the “Long Peace”. There are several reasons for this. Increased globalization in terms of trade and mutual commercial goals is a primary factor. There is also the relatively strong deterrent of nuclear war and mutually assured destruction, which has helped ensure peace over the past 8 decades. Mutual destruction, after all, does not sound like a lot of fun.

This might have instilled a false sense of security in many countries, swiftly exposed when regional powers had to start delivering aid to Ukraine. The thought of a largescale ground war had become so distant that many members of NATO realized that they were not that well equipped to fight one.

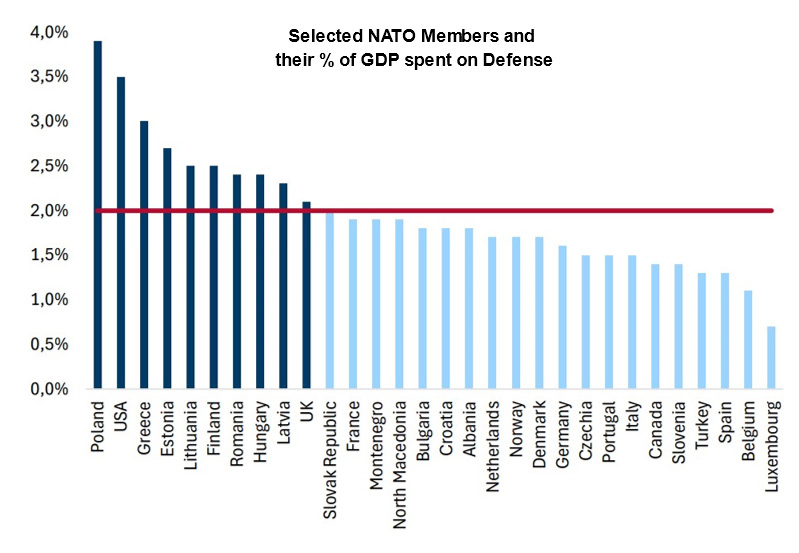

To ensure it is sufficiently armed to come to the defence of members when required, NATO put spending guidelines in place nearly two decades ago: 2% of each country’s respective GDP. The rationale makes sense. Countries with stronger economies would contribute a larger nominal amount, but proportionally the contributions would be fair. The problem with this guideline is that it was not being met. Not even close. In 2014, only 3 members met the contribution requirement, despite NATO Defence Ministers pledging more contributions as far back as 2006. 2014 proved to be a pivotal year in NATO’s history, as the “Long Peace” came to an abrupt halt when Russia illegally annexed the Crimean Peninsula. Understandably, this served as a wake-up call. Two years later there came another wake-up call, by the name of Donald Trump.

After the 2016 election of Donald Trump as the US President, and thus Commander-in-Chief of NATO’s most powerful member, those countries falling shy of the spending guidelines were given a thorough dressing down by Trump. This included some of the world’s most powerful countries and given the outsized role of the US in NATO operations, it was not as simple as brushing his criticisms aside.

Today, this is again relevant as Trump is very much part of the 2-candidate race for the 2024 US Presidential Election. If Trump is re-elected, there is likely to be increased pressure on NATO members that are not yet paying their dues, especially given the fact that Russia’s invasion came during a time when Trump was not president, something he is more than likely to make explicitly clear.

NATO wallets are opening

The results of Russia’s invasion, combined with Trump’s hardline stance, have been noteworthy. While only 3 NATO members reached the target spend level in 2014, this increased six-fold to an expected 18 countries in 2024.

While this is an improvement, a lot of investment is still required. After the ascension of Finland in 2023 and Sweden in 2024 to become fully fledged members, NATO now has 32 member states, more than 40% of which will not have met their spending targets in 2024.

Source: NATO, Flagship Asset Management

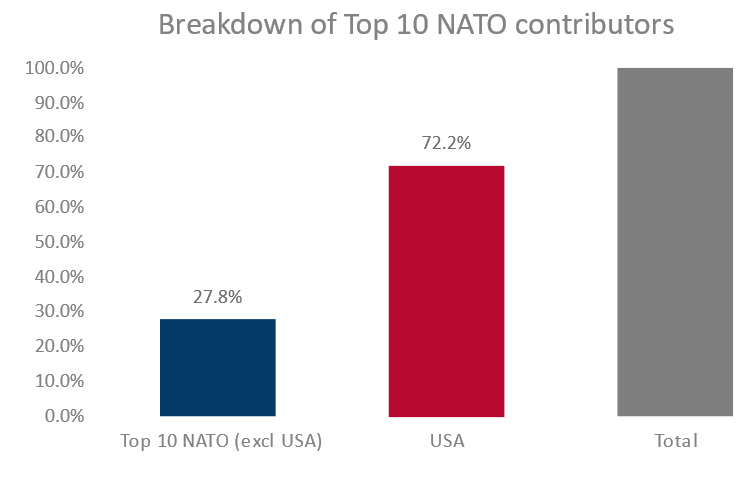

While the accompanying bar chart above gives the impression that the US is not that far ahead of peers in terms of military expenditure, the below provides a different perspective.

If Donald Trump, or any other US president, were to reduce contributions to NATO due to carrying an unfair burden of the expenses, this would leave a gaping hole in Europe’s defences during a time of increased global volatility.

Source: NATO, Flagship Asset Management

Effect on Capital Markets

As grim as the prospect of war is, and as much as military and defence investments are traditionally viewed in a poor light from an ESG perspective, they remain not only relevant, but necessary. Developments in recent years have cast a new light on investments in military and defence stocks. So much so, that some ESG investors have even started viewing these stocks more favourably, choosing not to exclude them based on ESG sentiment alone anymore, as they do play a role in protecting the very fabric of society.

Exposure to the structural growth story behind this theme can come in several different forms. One can either invest in traditional arms manufacturers or take a more subtle approach by investing in companies that provide auxiliary services, such as radar and electronic systems. There is also the option to invest in companies that have segmental exposure to the industry, without being dependent on it. All these sectors have experienced, and should continue to experience, increased military spending supported by a world simmering in geopolitical tension.

The past year has delivered stellar returns for global equities. Once markets inevitably cool down, and the lagging effect of high borrowing costs starts to bite, investors will have to look outside of the well-trodden IT sector for opportunities. This becomes slightly easier when considering investment opportunities which are set to benefit from structural tailwinds, even in times of geopolitical tensions and uncertainty.