09 Jan Voters turn their back on the economic status quo in 2024

As published in Business Day on 13 December 2024 By Philip Short

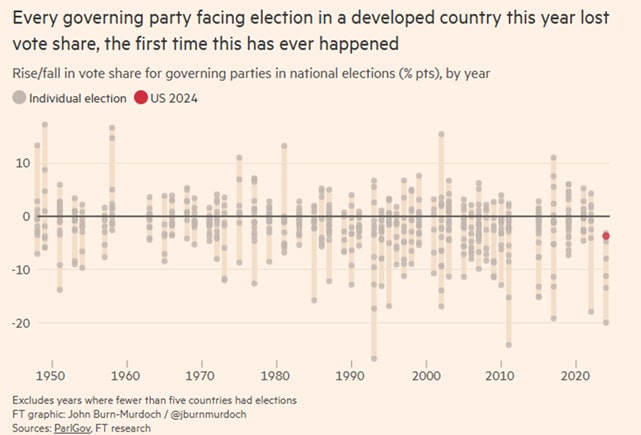

In 2024, the world witnessed a remarkable occurrence; every governing party in major developed countries that held elections lost the vote, a singular event in over a century.

From the United States to the United Kingdom, France to Japan, voters across the developed world echoed one sentiment: dissatisfaction with the status quo. The common thread? Economic hardships, inflation, and voters tired of governments perceived as ineffective in addressing the financial pressures on citizens.

The same was true of many developing regions that held elections this year, such as South Africa and Argentina. Elections are shaped by a range of factors, but besides the controversial issues, almost nothing compels voters to take action as much as pressure on their wallets.

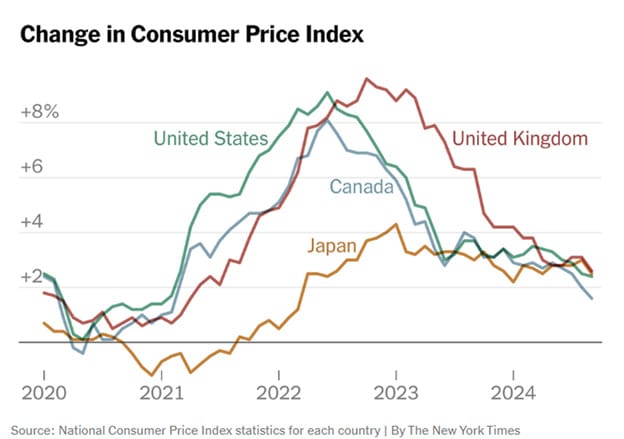

The most consequential election in 2024 was in the US, where the economic climate under President Joe Biden became a focal point for voter discontent. Despite a recovery from COVID-19, inflation reached its highest level in decades during 2022. The squeeze on household budgets, especially middle- and lower-income households, made it difficult for the Democratic Party to maintain its popularity.

President-Elect Donald Trump made sure to campaign on economic policies, focusing on local issues that affected consumers’ wallets. Even as inflation in the US retreated from its peak by the time elections were held, one must keep in mind that inflation is a rate of change. Thus, the cumulative effect on prices is still increasing, even if the rate of change today is slower than in prior years.

Many voters viewed the rising cost of living, especially the disparity between income and housing affordability, as a failure of government policies. All this while the US was spending billions of dollars supporting wars in other countries. It should come as no surprise that the economy was the top spot on voters’ minds when asked about the major issues affecting their voting choice in 2024.

The US government’s debt has been a key focus in the media recently, with Trump and Elon Musk positioning themselves as champions of reducing government waste, cutting regulation and simplifying bureaucratic processes while promising tax cuts. Their rhetoric resounded with voters as high inflation ate into their budgets.

Similarly, the soaring inflationary environment in the UK from 2021 to 2023, the highest this country has experienced in recent history, while perhaps not the death knell for the Conservatives, certainly did not aid their chances of winning this year’s elections. A string of Tory errors, compounded by four prime ministers in five years, Partygate, using taxpayers’ money to support the war in Ukraine, immigration issues and a collapsing national health system all contributed to ending 14 years in power.

The challenges at home in South Africa were slightly different but no less compelling. While inflation and the high unemployment rate certainly played a role in creating discontent, the country’s economic struggles were compounded by an entrenched culture of corruption within the ruling party and a perceived lack of reform. Voters’ frustration was not solely centred on inflation but was also fuelled by a government that had failed to deliver on promises of economic growth and job creation.

South African voters voiced their frustration with the ruling party during the run-up to the elections. Until recently, load-shedding became a metaphor for the broader inefficiencies of the government, as citizens felt the pain of poor governance in different aspects of their lives. Opposition parties gained ground by promising to fight corruption, reduce wasteful government expenditure and implement pro-business reforms. As in the US and the UK, voters in South Africa sought candidates who pledged to change the ruling party’s status quo. The message was clear: South Africans were tired of the government’s inability to create jobs and meet their needs.

Similarly, in Argentina, the surprise election results clearly indicated the public’s growing impatience with government mismanagement. This country, which has long battled escalating costs, saw a dramatic peak in prices in April 2024, with inflation reaching 292% at one stage. This was the culmination of decades of instability and government policies that failed to reign in rising costs, unsustainable public spending and excessive borrowing. The cost of living had become unbearable for Argentinians, and they were ready for real change.

Enter Javier Milei, a libertarian economist whose campaign was driven by ideas of radical economic reforms. He promised to slash government spending, eliminate wasteful bureaucracies, establish minimal state intervention and curb inflation. His policy ideas resonated with voters exhausted by economic struggles, particularly among young adults who had never experienced a stable economy. His outsider status and promises to dismantle the overblown public sector gave him a strong mandate.

Within months of taking office, Milei implemented policies to reduce inflation and kickstart growth. The impact was felt shortly afterwards, with inflation declining from its peak and early forecasts for 2025 predicting 5% real GDP growth. While the success of his policies and voters’ stamina to see this through remains to be seen, the message to the world was clear: Argentinians voted for radical change. Inflation, once again, was a key catalyst in this demand for change.

The golden thread connecting the election results in all these countries is the impact of inflation and economic hardships on voters’ perceptions of government competence. Although some of the drivers of inflation can be attributed to external factors, such as strong recoveries after COVID-19, abruptly interrupted supply chains, the war in Ukraine and an extended period of easy money (low rates), voters typically attribute a big portion of the blame to whichever political party is in power at the time.

The 2024 election results across the developed and much of the developing world reflect a deeper trend of discontent with governments that increasingly appear out of touch with the struggles of everyday citizens. In the US, high inflation contributed directly to Trump’s win. While not the overriding factor, the steepest inflationary environment for decades certainly aided the Conservatives downfall in the UK. In South Africa, voters were driven to demand more accountable leadership in the face of economic stagnation and corruption. The soaring cost of living in Argentina mobilized voters to seek radical solutions, choosing Milei’s extreme policies as the antidote. While the contexts may differ, one thing is clear – economies, and inflation, drive election results.

About the author

Phillip Short BSC (Maths) CFA

Fund Manager

Philip is a fund manager of Flagship’s global funds and brings specialist macroeconomic expertise.

Philip has gained 20 years’ experience in the industry at JP Morgan, Fairtree Capital and Old Mutual as an analyst and portfolio manager. He completed his Bachelor of Science in Mathematics at the University of Pretoria and is a CFA charter holder.