05 Apr Bottom fishing in emerging markets doesn’t always work.

As published by Sanlam Glacier on 1 Apr, 2022 by Pieter Hundersmarck

When PE multiples fall and never recover

There are two occasions when bottom fishing – or ‘catching a falling knife’ – doesn’t work.

The first instance is classic overvaluation, which is when the valuation of a share baked in over-zealous positive future prospects at the time you bought it. Because you overpaid, buying all the way down will rarely generate a great return unless you apply more than your initial capital (which few investors do). The second instance is when there is a structural shift in the way a geography or sector is valued by the market.

Be careful to buy overvalued stocks just because they have fallen ….

Cisco provides a very good example of the first. At the turn of the new millennium, the IT hardware, software and networking equipment company was one of the hottest stocks in the US stock market. From early 1999 to March 2000 the shares rose over 200 per cent to $80 per share, backed by euphoria for the technological shifts bought about by the internet. The thesis was solid: as a provider of networking equipment, Cisco was the “shovel-seller in the internet gold rush”.

But the thesis was also very well understood. At the March 2000 peak, Cisco’s P/E ratio stood at over 200 times. As the Dot-com bubble deflated, Cisco’s share price collapsed 80 per cent, a total market capitalisation loss of $431bn. Today, Cisco’s shares trade at $56 still 30 per cent below their peak reached over 20 years ago.

Changing narratives can permanently impair the earnings multiple the stock market will attach to a country

The second example of bottom fishing not working out is perhaps more intriguing. Structural shifts in the narrative around a specific geography can destroy market multiples as well as any reversion to mean argument. Russia provides a recent example of how this shift can damage portfolios. China provides a worrying example of another shift that may be taking place.

The popular investment narrative around emerging markets goes something like this: emerging markets are volatile and they go in and out of favor due to commodity and currency flows. Timing these various macro-related flows will allow you to reap generous rewards, or lose your shirt.

For example, commodity producers like Brazil, Russia and South Africa benefit from commodity price booms until their local inflation gets out of control and their currencies tank. Russian shares are a play on oil and gas-related revenues and their effect on the economy. Commodity importers, like India and Turkey, typically benefit from low oil prices and perform poorly when commodities rise.

Not all emerging markets are the same, and its high time investors stopped bundling them together. Besides their various commodity or economic blessings or curses, the main variance comes in the type of government, and the type of equity culture that this creates.

Equity culture covers two aspects. The first is the willingness and ability of a population to invest in equity as an asset class. Investors in many emerging markets typically put their money into tangible assets, such as real estate or gold, before they are lured into the financial market. As wealth rises, this changes. However, a lack of trust in regulation and financial institutions is one reason why emerging populations may be wary of financial assets.

South Africa, as well as Chile, are the rare exception to the rule. Retirement investment in individual capital accounts was made compulsory for Chilean workers in 1981. As a result, a local equity culture, which includes significant overseas investments, has developed. South Africa has one of the most developed life insurance markets which dates back to when companies like Old Mutual were founded, at the turn of the last century.

The second aspect is the regulatory and institutional environment that protect investments into financial assets. Most emerging markets are highly protectionist, domestically focused, and are overseen by considerable amounts of government intervention. In China, for instance, the state typically has a majority stake in listed companies, so there is at least the potential for a conflict of interest between the regulators and minority investors.

Democratic, capitalist countries like India and Brazil have a chance at becoming better places for equity cultures to thrive. Repressive regimes like Turkey, Russia and China offer far less opportunity for the required frameworks and trusted institutions to be created.

When these institutions are weak, or there is a risk that the conflict between State and shareholder is irreconcilable and subject to change at whim, then investors are on dangerous ground.

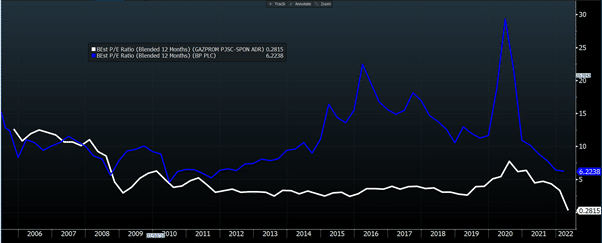

The largest stock in Russia, Gazprom, is a good example how narratives can change. When Russian stocks opened up for global investors in 1996, the first ten years saw the RTS index rise 2,662% to its peak in December 2007. Much of this was due to a low base effect as well as strong commodity prices. However, many Russian stocks also attained similar PE multiples to their developed market peers. Gazprom, in particular, began trading at over 11x earnings in 2006, which was on par to BP Plc.

Chart 1: The P/E (1 year forward) as well as the share price of Gazprom from 2006 – 2022

Chart 2: The P/E (1 year forward) of BP (blue) and Gazprom (white) from 2006 – 2022

However, things changed. In August 2006, the Yukos Oil company expropriation changed the risk appetite for Russia. The misalignment between the State and shareholders became obvious as Gazprom and other State-influenced firms pursued initiatives that marginalized shareholder interests. Even as commodity prices recovered post the Global Financial Crisis, Gazprom’s PE multiple sank to an average of 3.5x from that point on, never to recover.

The most recent example of the tension between the State and minority shareholders is Chinese equities. Investing in Chinese equities like Tencent, for example, require investors to differentiate between business specific risks (including structural changes that are occurring in the Chinese tech/gaming and e-commerce markets) and market risks (including the price/earnings multiples that Chinese shares should trade at relative to global peers. This can be a tricky call. Is the past a good indicator of what price/earnings multiples Chinese shares should trade on versus their global peers? An investor betting on the multiples of Russian shares in 2006 mean-reverting to their long-run average with global shares would have been spectacularly wrong.

China and Russia are not uninvestable per se. But things can change, and we have examples of what happens when they do. Certain geographies provide an altogether different risk profile beyond the risks apparent in developed equity markets. Investors need to know their risks, especially their tail risks, for when structural changes are happening.

Equity investing works over the long term primarily due to the institutional and regulatory bodies that protect equity as an asset class. They allow members of capitalist democracies to participate in the growth of their economies, and use that growth as a means to build capital for retirement. Since the US and Europe have a long history of equity culture, and their retirement funds, their pensions, and their foundations all invest in equities, there is a certain sense of ‘we’re all in this together’. Tail risks are lower.

In China, Turkey and Russia, none of these conditions hold. There are few large pension funds that need to invest in regulated equity markets to provide for citizens’ retirement. There aren’t many retail investors investing in their local markets. Instead, the main funder of retirement is the government pension system (which is effectively a claim on tax revenue). Equity prices are primarily a function of international investors dipping in and out of the country.

Could China be the next Russia?

Given the precipitous falls in Chinese stocks, there are many armchair investors who have been buying the dip, in the hope that their contrarian stance is proven correct. Things move in cycles after all, and the current disgust with Chinese shares due to heavy-handed regulation may also pass.

While they may be correct shorter term, for many investors, all the wrong lessons will be learned. As the chart of Gazprom shows, investing with the rear-view mirror offers false confidence. Russian stocks may yet recover, but the shares will most certainly trade at depressed multiples versus their previous levels. It would be interesting to see if Tencent ever trades at over 30x earnings again, as it did in the past.

About Pieter Hundersmarck:

Pieter is a fund manager and member of Flagship’s global investments team.

Pieter has been investing internationally for over 13 years. Prior to Flagship, he worked at Coronation Fund Managers for 10 years in the Global and Global Emerging Markets teams, and also co-managed a global equities boutique at Old Mutual Investment Group. Pieter holds a BCom (Economics) from Stellenbosch University and an MSc Finance from Nyenrode Universiteit in the Netherlands.